Table of Contents

Class 1

Class 2

Class 3

Class 4

Class 5

Class 6

Class 7

Class 8

Class 9

Class 10

>>Topical Articles<<

Assumed Longitude

Bowditch

Bygrave

Casio fx-260 Solar II

Emergency Navigation

Making a Kamal

Noon Sight

Pub. 249 Vol. 1

Sextant Adjustment

Sextant Skills

Sight Averaging

Sight Planning,

Error Ellipses,

& Cocked Hats

Slide Rules

Standard Terminology

Star Chart

The Raft Book

Time

Worksheet Logic

BCOSA.ca

Pub. 249 vs. Pub. 229 (See below re electronic calculators.)Your sextant is, at best, able to resolve angles of 1/10th of a minute, or 1/10th of a nautical mile. This translates into a distance of 202 yards, or 185 meters. An accuracy of 200 yards seems pretty impressive. However...

Refraction Issues

Because of the way the air bends light, particularly near the horizon (i.e. "unpredictable refraction"), celestial navigation has a theoretical accuracy of no greater than one nautical mile. This means that the 1/10th minute reading from your sextant is deceptive, since sights in practice can never be more dependably accurate than ±1 nm.

When you look at the horizon, it is not uncommon to see this sort of choppiness (analysis courtesy of here):

While these look like waves, the choppiness is actually a result of air refracting the light from the horizon differentially, as a result of variations in the temperature and humidity of various packets of air between the observer and the horizon. When this picture was taken, the distance to the building was known, as was the height of the tower above it. From this it was possible to determine that, in this case, the "wobble" in the horizon amounted to 0.8' of arc. In this case, that equates to an uncertainty in position of 0.8 nautical miles.

And it is occasionally possible to get truely weird and unpredictable refraction, which can throw off the apparent location of the horizon even further.

And there are other reasons why getting better than 1 nm accuracy from celestial navigation is inherently difficult.

Gravity Issues (Is "down" REALLY "down"?)

As Frank Reed has said,

"The Earth's gravitational field is a wobbly mess when you get down to coordinate differences smaller than about a mile. Astronomical navigation 'pulls down' the perfect coordinates of the celestial sphere, but it does so using the local vertical as a reference in nearly every case, and that local vertical is a property of the local gravitational field."

If you have ever been to Greenwich Observatory in London, and been surprised that when you are standing on the brass strip set into the pavement that traditionally defined 0° longitude, your GPS is actually NOT indicating that you are at 0.00°, then you have had occasion to think about this issue.

Greenwich Observatory did very careful astronomical observations of the heights of stars, using a bowl of mercury to define "horizontal". However, because of a local difference in the direction of gravity, that bowl of mercury was actually sloping ever so slightly.

As you sail up to islands in the Caribbean, the landmass of the island skews the direction of local gravity slightly. The ocean surface itself is not perpendicular to a line leading straight down to the center of the earth. It is sloping just slightly upward, towards the landmass of the island. This is enough to cause a celestial fix to differ by one or two nautical miles from a GPS fix.

Waves and Height-of-Eye Issues

The navigator needs to make a guess as to how far above water level his eye is at the moment he takes a sight.

Frank Reed has given an enormous amount of thought to the theoretical limits of sextant navigation. So we will once again quote him.

"Usually you make a rough guess by looking over the side at waves around your vessel, and you assume that waves a few miles away are similar. Then you do the calculation or enter the table with your height above that best estimate of the tops of the waves. No matter what, it's important to remember that the visible sea horizon is composed of a great many overlapping wavetops in a region about a mile deep (that is, when you're looking at the horizon, say, from a height of eye of 25 feet, you're looking through a zone that extends a mile deep from about 6 to 7 miles away from you).

"When considering your height of eye, you need to make an educated guess: what do you believe might be the height of those wavetops out there a few miles away in the distance? In addition, you need to make an estimate that's appropriate for the timing of your sights. If you're in a small sailboat in big waves, you may have to wait until you ride to the crest of a wave to take a sight. And then you have to make another guess: how does your height at that time compare to the tops of the waves in the distance? Are you atop an average wave? An above average wave? And is your boat heeling? Are you on the high side or the low side?

"The uncertainty of height of eye in dip calculations (or table lookups) is one of the key sources of system error in celestial navigation. There is no 'silver bullet' equation that will resolve this. The other key system factor is anomalous dip caused by small variations in refraction. In both cases, the sea horizon is the primary limitation in manual celestial navigation. If we can replace it, for example using a semi-inertial system for determining the vertical, then celestial position fixes jump dramatically in accuracy. Instead of +/- a mile, it's possible to achieve +/- 10 meters or better."

This is all part of the reason that Jerry Richter has said that "For a celestial navigator, a high tolerance for ambiguity is a useful personality trait."

If you would like to engage in the somewhat paradoxical pursuit of putting mathematical precision to all this ambiguity, look at the page on error ellipses.

Pub. 229/249 vs Electronic CalculatorsYou may wonder why we are using Pub. 249, Sight Reduction Tables for Air Navigation rather than Pub. 229, Sight Reduction Tables for Marine Navigation. Pub. 229.

For starters, these are both US Government publications. Hence the name "Pub". Many years ago, these were published by the US Hydrographic Office, and they were referred to as HO 229 and HO 249. Particularly if you are looking at older books about celestial navigation, you will seem them referred to that way.

Pub. 249:

- Is as easy as possible to use.

- Performs calculations to the nearest nautical mile.

- Works with the sun, moon, planets, plus stars that are directly overhead for those parts of the earth between N 29° and S 29°. There are 25 stars in this band that are bright enough to be used for navigation.

- Gives you all you need in two volumes.

Pub. 229:

- Is considerably more complicated to use.

- Performs calculations to the nearest 1/10th nautical mile.

- Works with the sun, moon, planets, plus all 57 stars that are bright enough to be used for navigation.

- Is made up of 6 volumes, meaning that it is more expensive, more bulky, and heavier to transport.

Given the uncertainty in the location of the true horizon, Pub. 249 in practice gives about the same accuracy as Pub. 229. This being so, its other advantages are felt by most recreational yachtsmen to make it the more desirable set of tables to use. The fact that there are a number of stars that cannot be used in fixes derived from Pub. 249 is not felt to be a big enough disadvantage to get into the complexity and expense of using Pub. 229.

I have used both Pub. 249 and Pub. 229 to reduce the same sights, comparing the two methods. The end-results were exactly the same, as they should have been. The big difference was that using Pub. 229 took several more minutes to work out the sight than it did to use Pub. 249.

The reason some prefer to use Pub. 229 still is that by doing all your calculations to the nearest tenth of a mile, you reduce the risk that the values you use may have their rounding errors all line up one way or the other, resulting in an error of as much as 1 nm.

In practice, your sights will not often accumulate rounding errors that all line up one way or the other. And in any case, if you are doing your sight reduction with a Casio fx-260 calculator, it deals in degrees to 8 decimal places, which effectively eliminates rounding errors completely.

If you are sailing from Hawaii to Canada, you can have an error of a mile (or 3 or even 10 nautical miles) and you still have sufficiently precise information to navigate. Once you get into the sight of land, however, an error of a mile one way or the other can be potentially life-threatening. So as soon as we can see land, we put our sextant in its box and use our eyes, the chart, depth sounder, compass, and radar to navigate.

A General Comment About Misleading Precision in Coordinates and CalculationsIn response to student feedback, Bob is transitioning away from the use of tables for sight reduction (e.g. Pub. 249) toward using an electronic calculator. The advantages of the calculator over books of tables are:

- The calculator eliminates one layer of abstraction, by dealing directly with your dead reckoning position rather than forcing the navigator to use an assumed position. This can make it easier for the novice to wrap his head around the overall task of celestial navigation.

- Bob can reduce a sight using a calculator in 1 ½ minutes less than he can using Pub. 249.

Given his susceptability to sea sickness, the less time Bob can spend down in the cabin, working up a fix, the better. Even saving a minute and a half will help.- A Casio fx-250 Solar II calculator can be purchased for $10 CDN...which makes it vastly cheaper than purchasing volumes 2 and 3 of Pub. 249, at $33 each, plus shipping.

- Being solar powered, a Casio fx-250 never needs to have any batteries replaced.

- A Casio fx-250 Solar II can be used while one inch underwater. So it is more resistant to salt spray than a volume of tables published on paper.

- A calculator is superior to Pub. 249, in that it can be used with all 57 navigational stars, plus planets/sun/moon.

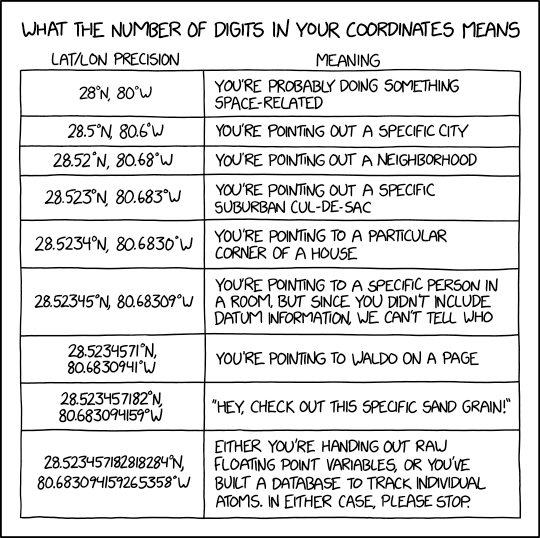

- In doing all calculations to 10 significant digits, a calculator gives you a deceptive idea of the kind of accuracy it can deliver (see below). That said, you can be confident that you have eliminated any rounding errors that might reduce the accuracy of your fix.

The disadvantage of a calculator is that it is susceptable to being fried by the EMP of a lightning strike to the mast. This disadvantage may be addressed by purchasing two or three calculators (at $10 each) to keep on board, at least one of which should be stored in a Faraday cage (see http://bcosa.ca/Class2019/EmergencyNav.htm).

Bob had thought that using a calculator for sight reductcion would have too great a learning curve on the new learner. However, one of Bob's students who is a professional artist, and a woman with a self-described "math anxiety", found doing sight reduction easier with a calculator than with Pub. 249. Consequently, Bob believes that he can teach ANYbody to use a calculator...and have them find it eaiser than learning to use Pub. 249.

Why Nautical Miles Rather Than Kilometers?Courtesy of https://xkcd.com/2170/...

Celestial navigation works because of its use of trigonometry: sines, cosines and the like. One can work out sights, in fact, without using Pub. 249/229 at all...using only a hand-held calculator, doing the math manually.

One nautical mile (abbreviated nm or NM) is the length of one minute of latitude. Further, the magic of using a sextant on an (almost perfect) sphere, is that you can equate sextant angles to distances. That is, if your actual sextant angle is 6 arc-minutes greater than your calculated height, you are 6 nautical miles away from your dead reckoning position.

This is a key reason why navigators use nautical miles instead of kilometers. If 1 nautical mile = precisely 1 minute of latitude, calculations become simple. Converting to kilometers would be simply one more step...one more opportunity to make an error. It is simply easier to use nautical miles.

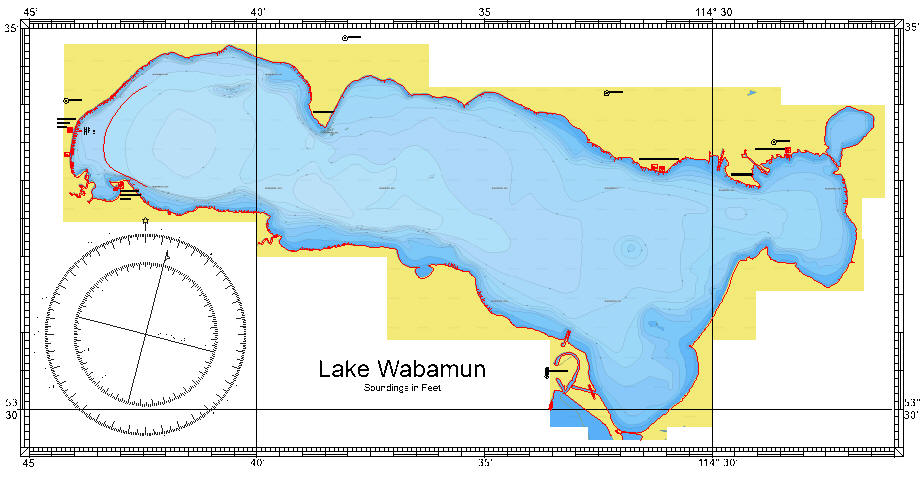

Further, there is a world-wide assumption that navigators (either marine or aviation) will use nautical miles. You can see this assumption in the number of charts that have latitude and longitude along the outside edge, and do not bother to include a scale-of-distance on the chart. The idea is that if you have latitude listed alongside the margins, you have no NEED of a separate scale-of-distance.

Here is a chart from a Canadian lake where the chart makers assumed that the users would be working in nautical miles. Notice the absence of any scale of miles or kilometers. In this, nautical charts are quite distinct from road maps used by automobiles.

Even if we use sight reduction tables rather than doing the math by hand, the equivalence of nm and minutes of latitude still makes the paperwork associated with navigation easier to do.